The success factors of Amsterdam

Between the mid-1300s and a century later Amsterdam changed drastically. At the time the Miracle took place Amsterdam was a village of about 1,000 residents. It was a rather rural, self supporting community of fishermen, farmers and some craftsmen. One hundred years later the settlement had expanded with two new rings of canals quadrupling the population. The harbour became an essential hub between the two major economic powerhouses of that time: Hamburg in the North and Bruges in the South.

More importantly, the settlement and its dwellers started to break free from the feudal system that dominated in medieval Europe. The start of a pre-modern society.

There were a number of reasons for this success. In this blog we will discover several of these success factors. But first we take a look on how Amsterdam looked like around the year 1345.

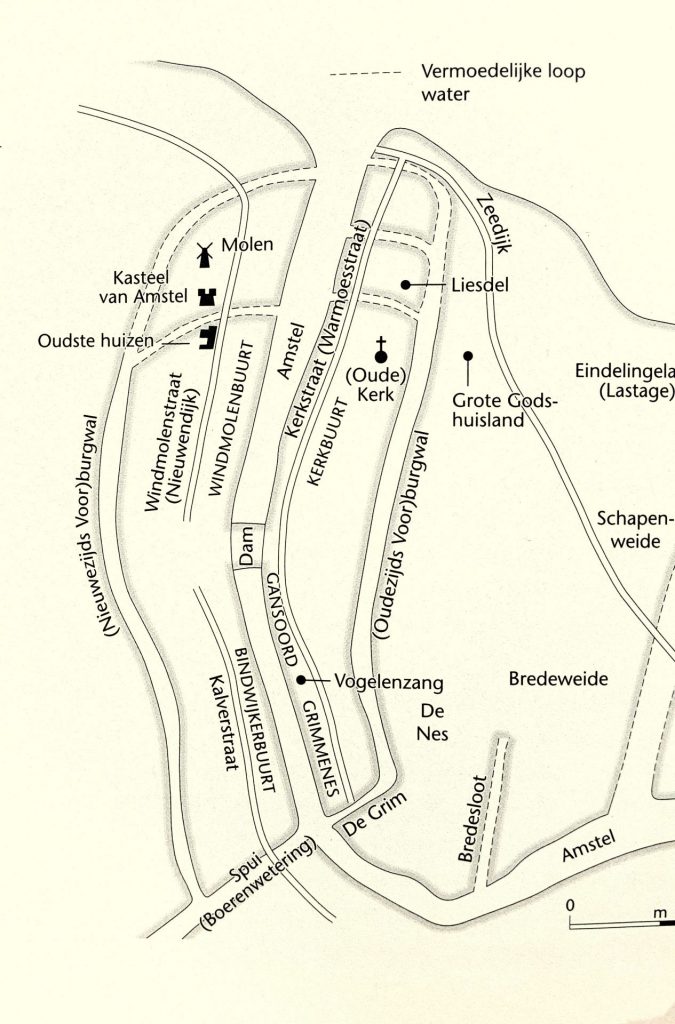

H-shaped Amsterdam

Around the year 1345, the small areas on both sides of the Amstel started to join together in an H-shaped town. The Miracle of Amsterdam took place in Kalverstraat. Read more about what exactly happened in our earlier blog. This Kalverstraat was the main street in the neighborhood called Bintwijk, south of the Dam on the westbank of the Amstel. The name is derived from its location, ‘wijk’ meaning neighborhood – ‘binnen’ – safely within the protection of the dam in the river Amstel, now known as the Dam square.

North of the Dam – outside of the Dam square – the street continues as Nieuwendijk. At the north end of this river dike a windmill gave the name to this settlement: Windmolenbuurt. Not far from this windmill the oldest evidence of human settlement has been found, dating back from the 1200s, and also the foundations of the alleged Lords of the Amstel castle. See older blog post about the Amstel family. So the Nieuwendijk – New (river-) dike – may as well be the oldest street of Amsterdam.

Across the Amstel the Kerkbuurt – Church quarter – was located near the Saint Nicolas church (now Old Church) on the East bank of the Amstel. Heading southwards the Eastern river dike now called Warmoesstraat crosses the Dam and enters the neighborhoods Gansoord and Grimmenes. The latter is probably a contraction of the river dike Nes and the waterway Grim: ‘Grim and Nes’.

Now, let’s go back to the success factors of Amsterdam.

Urbanisation in the Lowlands

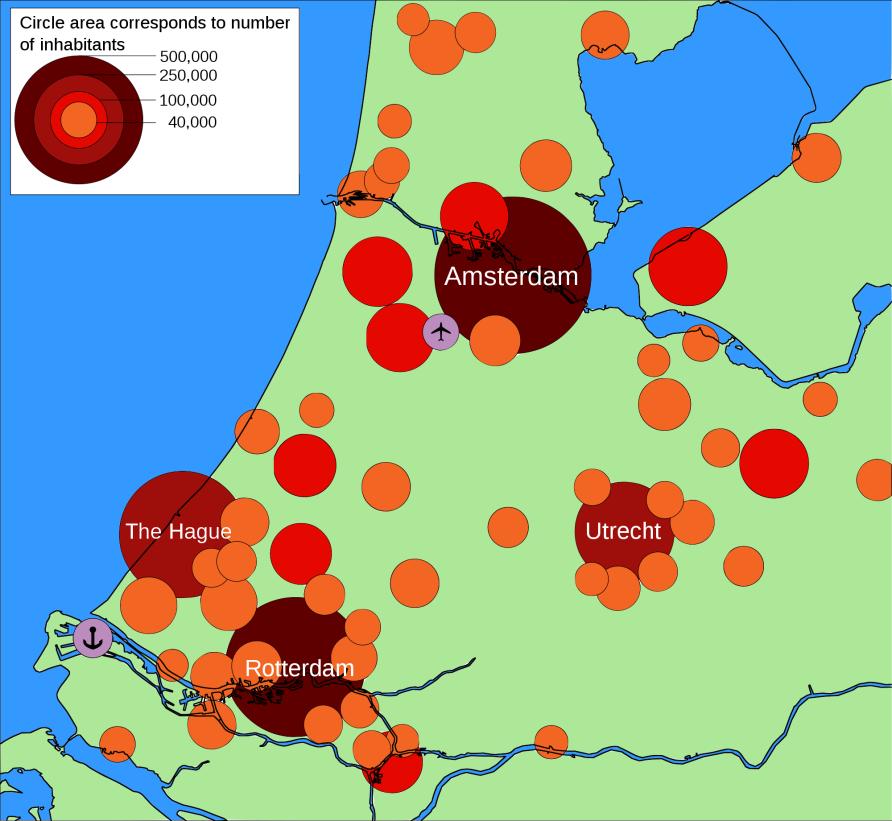

Settlements along a river dike were very common in the watery Netherlands: a safe, high and dry location. The river dam was the social and economic center of the community, where waterways crossed roads on land. A perfect place for a market and a harbor. This explains the names of many towns and cities in Holland that arose around the same 1300s: Rotterdam, Amsterdam, Zaandam, Edam, Volendam, Durgerdam. All those dam(n) cities.

By the early 1500s Holland was one of the most urbanized areas of Europe. Still today most people in the Netherlands live in this west side of the country, the so called Randstad – or Ring of Cities – comprising Amsterdam, Haarlem, Leiden, The Hague, Delft, Rotterdam, Gouda and Utrecht. Let’s zoom in on this spectacular metamorphosis.

The rise of the peasant class

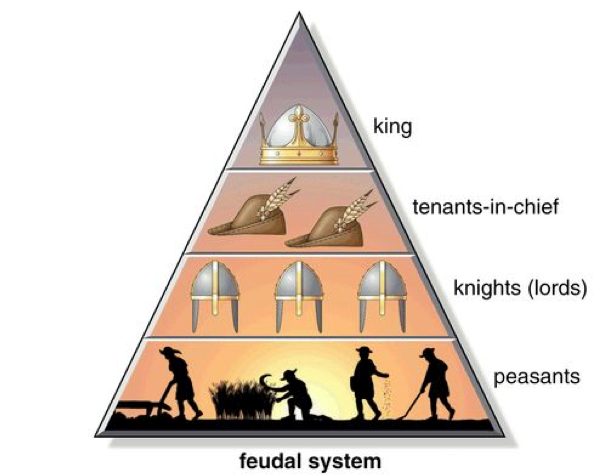

Medieval Europe was quite a strict ordered society. The so called feudal system formed a clear triangle of power: The aristocratic landowners in their strongholds and castles (counts, dukes, kings), the clergy of the church in their monasteries and cathedrals, popes (arch-) bishops, and peasants and craftsmen in their thatched huts, the latter being serfs or rather slaves to the previously mentioned aristocracy.

In the swampy west of the Netherlands, Holland and Zeeland, this feudal system didn’t work well. The terrain was too wet for farming and therefore for feeding the ever-growing population. The Counts of Holland took a bold chance to slowly steer away from the feudal system in favour of a more practical model. Peasants were given the chance to create their own land out of the boggy wetlands. In return they were given a lot more freedoms and ownership. Peasants became landowners and slowly the aristocracy were pushed into a more equal role.

The Dutch Polder model

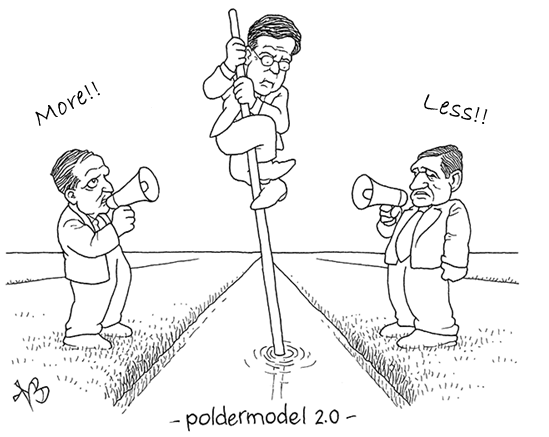

This lack of an aristocratic tradition explains the lack of impressive castles and palaces in the Netherlands, unlike its German, French and British counterparts. It also explains the deeply rooted cultural habit to transcend hierarchy in order to negotiate a workable compromise together. This consensus-driven business mentality is called the ‘Polder model’. A polder is reclaimed land, a former lake or swamp, mostly below sea level. As we’re all in this together, collaboration with all stakeholders is key, regardless your social status or background. There is a theory that claims there is a link between egalitarian societies and the flat terrain conditions in which they tend to thrive.

The rise of the peasant class also ushered more independence for cities. The Counts of Holland offered all kinds of trade privileges to cities, like the Toll privilege being the oldest document mentioning Amsterdam in 1275. This way the local aristocracy changed the medieval rural-orientated feudal system for a more urban-orientated system. The Counts of Holland built their castles inside, or close to their cities. The current city hall of Haarlem is a good example of such a city castle. In The Hague the Count’s hunting ground retreat now forms the centrepiece of the Dutch Houses of Parliament: The Hall of the Knights.

Maritime revolutions

At the same time, people in this river delta/lake district searched for food outside of their region. The Dutch soil did not produce enough food to feed the people. Fish from the North Sea was the first step in addressing this problem. Herring was a dominant part of everyone’s meal. Three successive inventions would create a maritime revolution for the Dutch. The were the most important success factors of Amsterdam.

First they invented a new and larger type of fishing net; the so-called ‘Fleet’. In fact the ‘fleet’ was a series of about 100 nets forming an underwater curtain of several kilometres. This meant a boom in the efficiency of fishing.

Secondly a proces called ‘gibbing’. From the caught herring its gills and part of the gullet were removed, the herring was salted and put in barrels. The Dutch discovered that this way the herring could be preserved for a longer period. Not a couple of weeks but almost a year. This discovery would extend the market for herring tremendously. Eventually this salted herring and this process of gibbing – ‘haring kaken’ in Dutch – would make it possible to make much longer voyages at sea.

The third invention was a new type of vessel. This meant no less than a maritime revolution. This Herring Buss was slightly larger than the earlier mentioned Cog ship and worked as a factory at sea. The process of ‘gibbing’ now could take place on the ship itself, without losing time with going back to a harbour.

Soon after these discoveries Dutch ships made it to the Mediterranean – for more salt – and as far as Denmark for the rich fishing grounds.

New trade routes

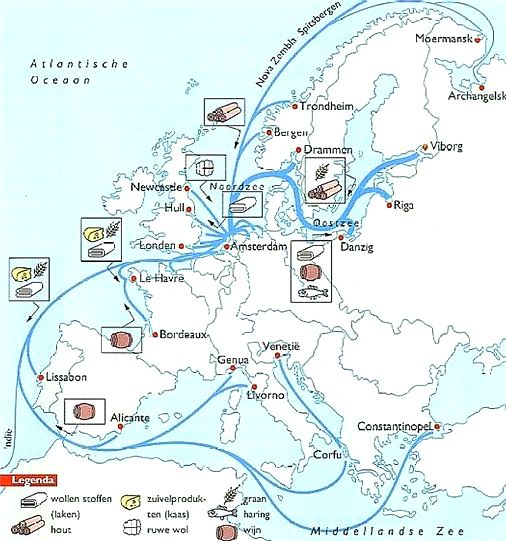

Most vessels, however, would prefer the safer inland waterways. The Holland waterways were ideal for the trade between the two largest economic powerhouses of the late middle ages: Hamburg and Flanders. Hamburg in today’s Northern Germany was the leading city in the so-called Hanseatic League. A trade league of cities in Northern Europe, predominantly North Sea and East Sea oriented cities. A harbour city where all the riches of the Baltic states and Scandinavia were stacked up: beer, timber, grain, wheat, rye.

South of Holland and Zeeland was the wealthy region of Flanders. Cities like Bruges, Ghent and later Antwerp had formed the richest European region in the late Middle Ages. These cities had links with the Italian city-states like Florence and Siena. They brought Flanders to the verge of their own renaissance period offering more refined products like cloth and tappistry.

The Holland waterways were crucial links between the two wealthy regions. Amsterdam’s harbor became the northern gate into the Hollandic inland waterways. Here the barrels of Hamburgian beer transferred from seafaring ships into the smaller vessels for the freshwater inland waterways towards Flanders.

Gradually the Amsterdam skippers took over the inland waterways from the Flemish, and the North Sea (and later even the East Sea trade) routes from the Hamburg sailors. Trade on the East Sea brought in the vital grain to feed the Dutch. Therefore the Dutch called it the ‘moedernegotie’ – or the Mother of all Trade, essential for the later emerging Dutch Empire.

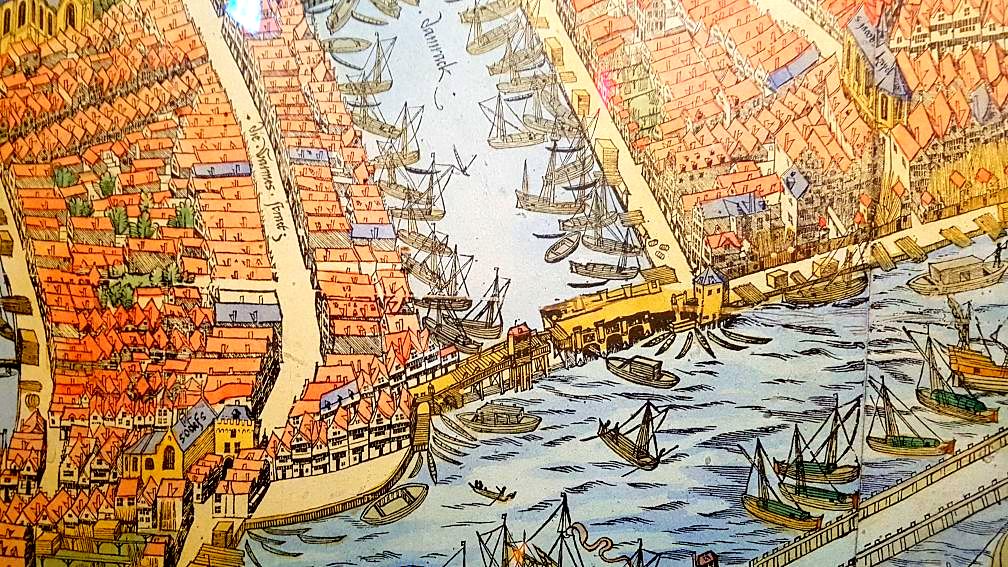

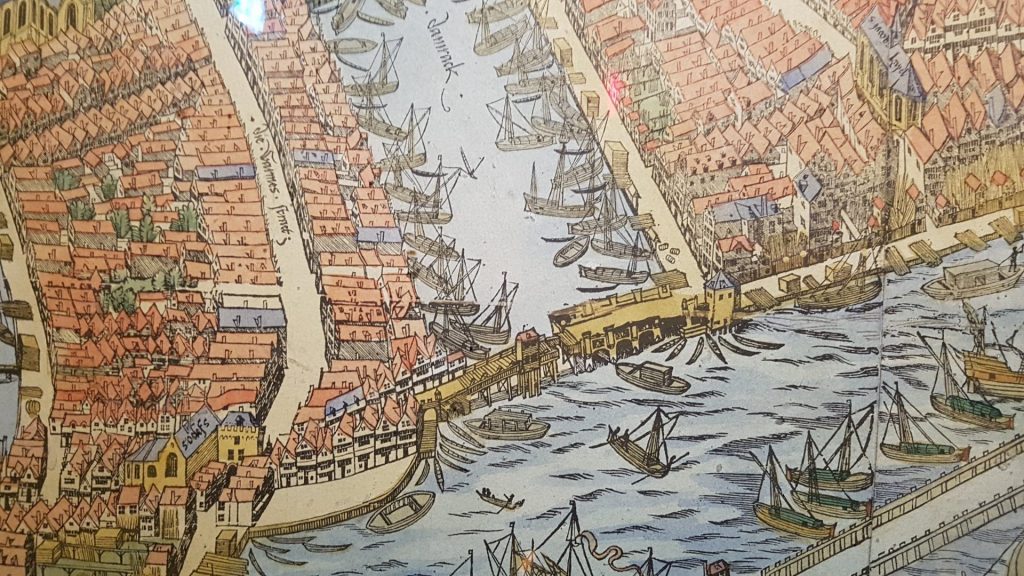

A modern harbor

Needless to say the Amsterdam harbor exploded in size and importance in the 1300s. This was the triangle which today comprises the full width of the Central Stationa pointing towards the Dam. The T-shape of the Amstel mouth, protected by a mile-long line of wooden pillars in the water of the IJ. Imagine a forest of sailing masts, dozens of carriers, porters and sailors on the quays. Barrels being hoisted up into the warehouses right at the waterside. Flanders’ cloth for Hamburg, Hamburg beer for Flanders, Bordeaux wine for England, British wool for Danzig, Polish grain for the Dutch and Dutch herring for all.

To say Amsterdam started as a fishing village doesn’t do justice to its origins. The strategic river mouth grew in to a fully equipped trade hub; the warehouse of Europe. More and more harbor-orientated craftsmen settled their industry near the harbor, near merchants from all over Europe holding an office here in this pre-modern mercantile society. A good example of such a trade post is the building called ‘The Weapon of Riga’ with the coat of arms of the Latvian capital Riga prominent on the facade; a beautiful early 17th century Dutch renaissance house for a rich Baltic merchant.

Water management

The Dutch are known worldwide for their fight against water. One of the twelve provinces that make up the Netherlands is even called Zeeland; Sea Land. It is a river delta highly vulnerable for floods. In the fast growing Amsterdam water became a problem as well. During the 1300s the previously mentioned neighbourhoods around the Amstel had grown into one single town.

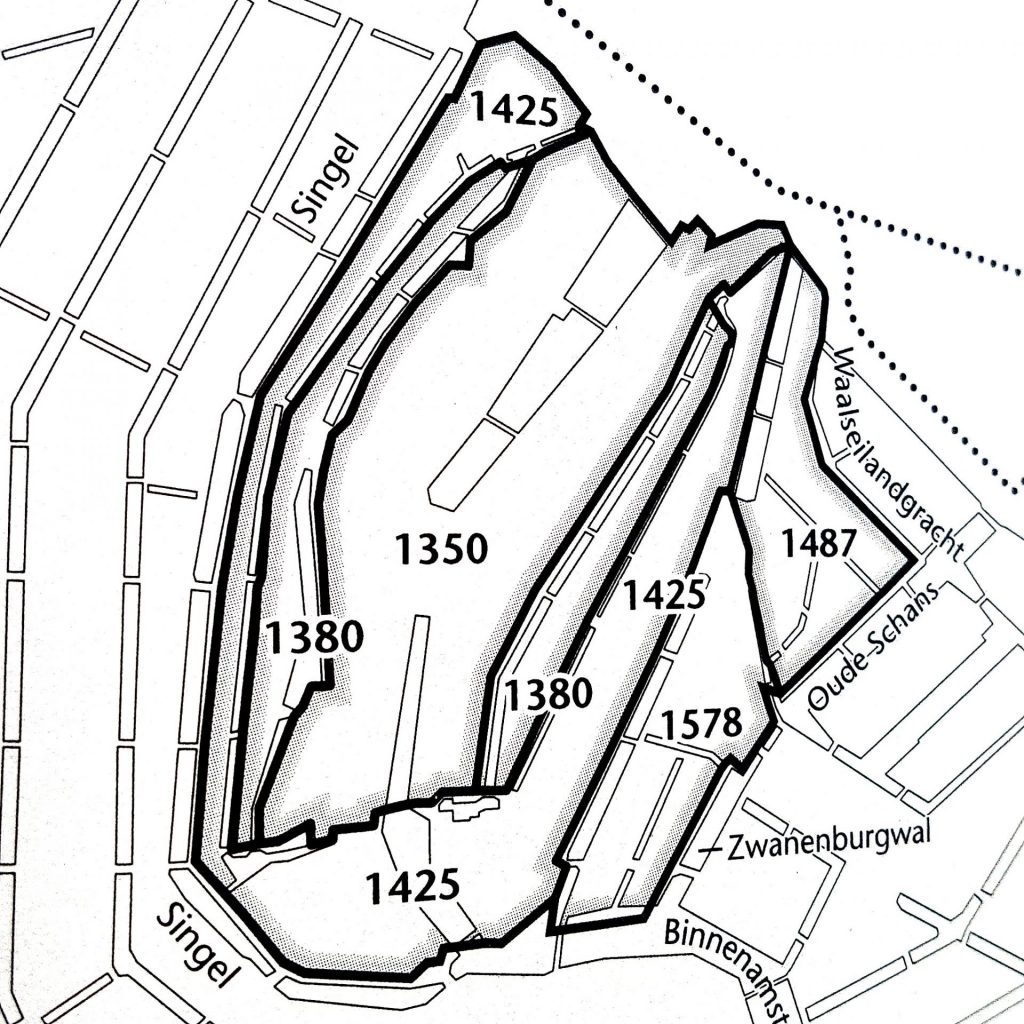

Soon the river dikes became too small for the ever growing community. People started building in and on the river, narrowing the flow bit by bit. Today you can still see the warehouses with their feet in the water as you walk from the Central Station towards the Dam. The now remaining water used to be about five times wider in the 1300s. This resulted in several small floods of the river. Two canals were dug on both sides of the Amstel to divert the water. Several decades later another set of canals were dug for the same purpose, extending the city in the shape of a sliced union: layer by layer. Water would not be the only threat to this thriving boomtown. More about another major challenge in our next blog.

Conclusion: Action and reaction

So the success factors of Amsterdam were in fact a whole set of interconnected factors: no rise of the peasant class without the boggy terrain, no consensus-driven Polder model without a common interest of keeping our feet dry, no mercantile cities without a strategic system of waterways, no innovations like the Herring buss and the staple market without intensive contact abroad. This chain reaction makes it hard to put a finger on a single crucial success factor. I’m sure the Dutch will negotiate a workable compromise.