Thus far in this blog series about the history of Amsterdam we have not mentioned many buildings that still can be seen in today’s Amsterdam. The reason for this void is simple: Medieval Amsterdam was generally a wooden city. The first stone building would have been the Oude Kerk, and later the Nieuwe Kerk, their late medieval Gothic pinnacles mounted high above a vast ocean of thatched roofs and timber structures. Let us give a reconstruction of Amsterdam in the 1400s. How did the city smell, sound and look?

A forest of masts

Being a harbour town, most people would enter Amsterdam on the same location as most visitors today: at the mouth of the river Amstel, looking south towards the Dam square. Picture water instead of the artificial island upon which the train station is built in the 19th century. A busy stretch of water, loaded with dozens of small and bigger vessels. A forest of masts and ropes of ships from all over Europe would have taken your sight of the Amsterdam skyline.

Above the west bank of the Amstel – now Victoria hotel – you may spot swarms of loud crying seagulls circling over the fishing quay. Fishermen unload barrels of herring, cod and eel from their ships and roll them along over the unpaved street towards the row of pointed warehouses. Imagine a thick salty smell of fish and sweat. Today a narrow alley testifies to bustling fishing industry in this area: Haringpakkerssteeg – Herring Packer Ally. Later on a defence tower nearby was named Haringpakkerstoren – Herring Packer Tower. A block away from the quays you’ll squeeze through the narrow alleyways and ascend the river dike, the Nieuwendijk.

Pigs and blacksmiths

By the end of the 1300s the rural feel of farms, barns and backyards had made way for a more densely packed city. The extensive farm plots had been divided into several separate building plots. Narrow alleys gave access to the newly created homes in the back. Some of these alleyways still testify to this day to the owners of these 13th and 14th century dwellers, like the Dirk van Hasseltsteeg and the Heintje Hoekssteeg named after Dirk van Hasselt and Heintje Hoeks.

In spite of this early stage of urbanism the signs of farm life ware never far away. Depending on the weather you walk through the muddy or dusty 15th century Amsterdam streets. You’ll be accompanied by pigs, dogs and chicken wandering around freely. Hygiene wasn’t a big thing back in those days. However, this Nieuwendijk, the winding river dike adjacent to the Damrak, was also a centre of craftsmanship. Archeological diggings have surfaced traces of shoemakers, blacksmiths, timber workers, rope, barrel, sail and fishing net makers. Small businesses all more or less aligned with shipping and trade. It must have been a noisy and smelly street, cramped with wooden facades leaning forwards and sideways.

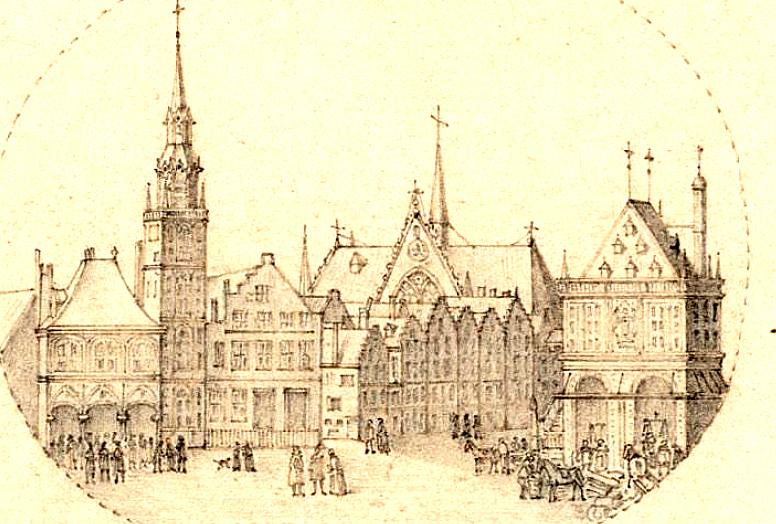

The Dam

On the other end of the river dike you’ll enter an open space and the city’s most important building: the first city hall, testifying to the new status of the young city since 1385. This small gothic styled structure was the administrative, legal and governmental center of the community. It was located roughly in front of the current Royal Palace, aligned with the Nieuwendijk and the Kalverstraat. The only 15th century building that survived the ages is the Nieuwe Kerk.

The Dam is often called the Dam square. Until the late 1800s the function of river dam, a water barrier to prevent floods, could still be recognized. The place was literally called ‘Die Plaetse’ – ‘the place’ and was a lot smaller than today’s Dam (square). Yet it was the centre of social and commercial activity. You could mingle in the hustle and bustle of the fish market or the market for young cows a bit further in the street that now is called Kalverstraat – Calf street, still one of Amsterdam’s main shopping streets. From when the first records began, the city developed economically very rapidly; a boomtown full of energy and perspectives.

Amsterdam on Fire

The big setback came in the summer of 1421. The thatched roofs above the blacksmiths were warm and dry. It’s hard to retrace where exactly the fire broke out. The jam packed timber town was an easy target for the fast spreading flames.

There was not much the people could do about it. Until Amsterdammer Jan van der Heijden invented the fire engine in 1690, buckets with canal water had to go from hand to hand making their way to the flames.

More fire

On May 25 to May 26 1452 an even bigger fire scorched the city, flattening about three quarters of Amsterdam. The Oude Kerk miraculously survived both fires. The city hall however as well as the Nieuwe Kerk, which was still under construction, both burnt to the ground. Innumerable invaluable documents were lost for eternity.

Amsterdam laid to rubble and building had to start from scratch again. This time with a new rule: houses should at least have brick side walls, if not built all in stone. Given the devastating impact the flames must have had, it’s remarkable how few records have survived about the process of rebuilding the city. It does give you the answer why so far this blog series about the history of Amsterdam hasn’t mentioned many buildings that can still be admired today.

Eternal contest: Amsterdam’s oldest house

Historians, architects and archaeologists in Amsterdam share a favourite debate when it comes to the question of the oldest house. Heated discussions by grey haired bookworms waving old city maps, claiming statements supported by elaborate PowerPoint presentations.

The Oude Kerk – dating back from 1306 – is by far the oldest building of Amsterdam, no question about that. For many years two candidates strove for the honour of being the oldest house: Zeedijk 2 and the ‘Wooden House’ in the Beguinage. Both mansions are built after the second city fire of May 1452, given the brick side walls flanking the city’s only two wooden houses with a wooden facade. The two structures both lean forward on purpose, which was a common way of supporting the wooden skeleton of the structure. Both the current cafe on the Zeedijk and the house across the English Reformed Church show late medieval elements on the inside.

And the winner is…

Two modern techniques could point out a winner between the two houses: C-14 carbon dating and a dendro-chronological study: the year rings of wood make a sort of barcode revealing the age of the used tree. Zeedijk 2 must have been built between 1540 and 1550, and the Houten Huis on the Beguinage around 1530.

Ironically a fire elsewhere in the city pointed out a 3rd candidate as winner. In 2012 a fire broke out in a house in the Warmoesstraat, some 300 meters from the Zeedijk 2. While checking the damage in a neighbouring attic behind an 18th century facade on Warmoesstraat 90, archaeologists made a pivotal discovery. They stumbled upon a medieval wooden roof structure dating back from 1485! This makes Warmoesstraat 90, today a gay orientated leather shop, the oldest house of Amsterdam.